Today's the big day. I'm getting ready to hit the publish button to send my translation of the Carmen off to Kindle for publication. So I guess this first post to the blog is about why I did it.

There is only one contemporaneous account of the Norman Conquest: Carmen de Normannicum Conquestum or The Song of the Norman Conquest. The Carmen is an 835 line untitled epic poem attributed to Guy de Amiens, Bishop of Amiens, probably penned in early to mid-1067. He drew on eyewitness accounts of the events depicted, and dedicated the resulting poem to Lanfranc of Pavia, Abbot at the Abbey of St Stephen at Caen in 1066 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1070. Lanfranc had accompanied William the Conqueror throughout the conquest as an advisor on religious and political matters. He was in a position to have observed first hand all the events described, and indeed, may have been one of the sources for Guy de Amiens in compiling the conquest story. Lanfranc is invited by Guy in the dedication of the Carmen to amend his draft to make it acceptable for publication to the world. For these reasons, the Carmen is broadly regarded as providing the most authoritative account of the Norman Conquest.

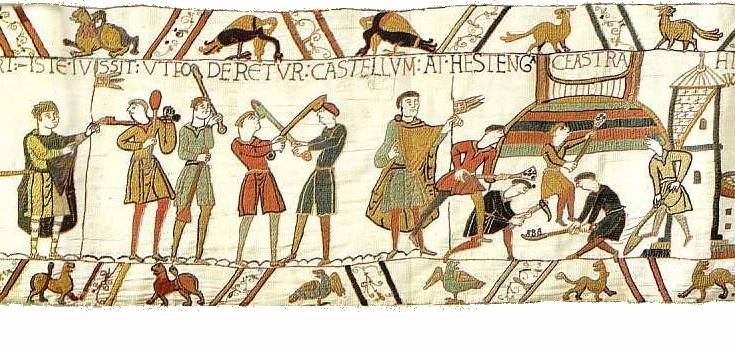

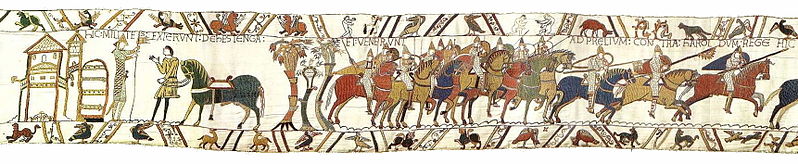

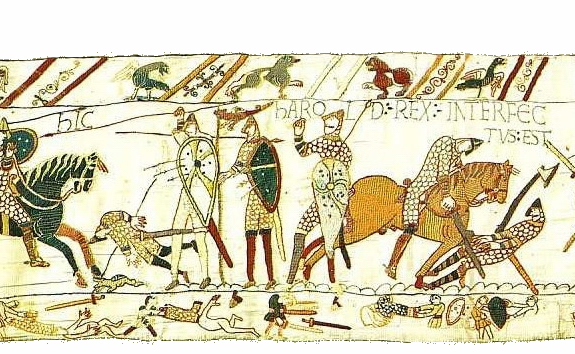

The Carmen only exists now as one Latin manuscript in Medieval Latin miniscule script on vellum, with a further fragment of the first 66 lines, in the Royal Library of Brussels. It is a very fragile record of the great events of 1066. Years later the Bayeux Tapestry would depict the same scenes, but that is the graphic novel version of the conquest story. It is the Carmen alone that offers the official record. Every word has weight, every line has import.

The image below approximates the actual size of the Carmen manuscript:

I started my own English translation frustrated by the quality of the 1972 translation published by Oxford Medieval Texts. The translators missed a lot of context, and good translation requires context. I am sympathetic that theirs was a fair effort, but modern techniques make a better translation possible and perhaps inevitable. And I rejected utterly their tortured punctuation in favour of a much simpler model. While there is no punctuation in the original text, it seemed to me that the author had carefully scripted and delimited his ideas line by line. Once I grasped the tight and elegant structure of the Carmen, if my English jarred, I knew it was wrong.

I began working through a few lines at a time just for fun, to discover for myself the meaning in key scenes of the Carmen. Soon it was an obsession to unlock all the meaning and make it accessible in English to a wider readership and wider scholarship. I hope the result is a cracking good read that will be enjoyed by everyone who comes to it, whether Latin scholar, armchair historian, battle re-enactor or student.

When it originally appeared in a French collection of Anglo-Norman Chronicles it was styled Carmen de Hastingae Proelio - the Song of the Battle of Hastings. A further transcription a decade later title it Carmen de Bello Normannico - Song of the Norman War. I do not regard either of these earlier names as accurately capturing the scope of the Carmen. The Carmen provides an account of the Norman Conquest from departing Dives to St Valery-sur-Somme to the a camp and fortress on the Sussex coast to the bloody battlefield to Hastings to Dover to Winchester to London to Westminster. It encompasses everything from the preparation of the fleet to the coronation of William the Conqueror. It offers history, religion, blood, plunder, politics and conquest. For these reasons I am giving my translation of the Carmen the bigger and more accurate title: Carmen de Normannicum Conquestum - The Song of the Norman Conquest.

As I began to put history to the narrative of the Carmen, many surprising facts came to light, and many surprising patterns emerged. Some of these facts will be at odds with the received wisdom and general understanding of English history about the conquest. That is unfortunate, but progress requires the recognition of error. The Carmen is very likely right, and history as it is taught is very likely wrong. So much of what we think we know is what we choose to know. Perhaps it is time to offer a wider choice that places English history in a wider context, painted on a wider canvas.

My translation of the Carmen makes the following revelations:

The objective of this blog is to provide a forum for sharing ideas and evaluating theories that emerge as the Carmen reveals its own truth about the events of 1066. In like spirit to Guy de Amiens, I am happy to learn from others and to open my work to collaboration and supplement.

There is only one contemporaneous account of the Norman Conquest: Carmen de Normannicum Conquestum or The Song of the Norman Conquest. The Carmen is an 835 line untitled epic poem attributed to Guy de Amiens, Bishop of Amiens, probably penned in early to mid-1067. He drew on eyewitness accounts of the events depicted, and dedicated the resulting poem to Lanfranc of Pavia, Abbot at the Abbey of St Stephen at Caen in 1066 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1070. Lanfranc had accompanied William the Conqueror throughout the conquest as an advisor on religious and political matters. He was in a position to have observed first hand all the events described, and indeed, may have been one of the sources for Guy de Amiens in compiling the conquest story. Lanfranc is invited by Guy in the dedication of the Carmen to amend his draft to make it acceptable for publication to the world. For these reasons, the Carmen is broadly regarded as providing the most authoritative account of the Norman Conquest.

The Carmen only exists now as one Latin manuscript in Medieval Latin miniscule script on vellum, with a further fragment of the first 66 lines, in the Royal Library of Brussels. It is a very fragile record of the great events of 1066. Years later the Bayeux Tapestry would depict the same scenes, but that is the graphic novel version of the conquest story. It is the Carmen alone that offers the official record. Every word has weight, every line has import.

The image below approximates the actual size of the Carmen manuscript:

I started my own English translation frustrated by the quality of the 1972 translation published by Oxford Medieval Texts. The translators missed a lot of context, and good translation requires context. I am sympathetic that theirs was a fair effort, but modern techniques make a better translation possible and perhaps inevitable. And I rejected utterly their tortured punctuation in favour of a much simpler model. While there is no punctuation in the original text, it seemed to me that the author had carefully scripted and delimited his ideas line by line. Once I grasped the tight and elegant structure of the Carmen, if my English jarred, I knew it was wrong.

I began working through a few lines at a time just for fun, to discover for myself the meaning in key scenes of the Carmen. Soon it was an obsession to unlock all the meaning and make it accessible in English to a wider readership and wider scholarship. I hope the result is a cracking good read that will be enjoyed by everyone who comes to it, whether Latin scholar, armchair historian, battle re-enactor or student.

When it originally appeared in a French collection of Anglo-Norman Chronicles it was styled Carmen de Hastingae Proelio - the Song of the Battle of Hastings. A further transcription a decade later title it Carmen de Bello Normannico - Song of the Norman War. I do not regard either of these earlier names as accurately capturing the scope of the Carmen. The Carmen provides an account of the Norman Conquest from departing Dives to St Valery-sur-Somme to the a camp and fortress on the Sussex coast to the bloody battlefield to Hastings to Dover to Winchester to London to Westminster. It encompasses everything from the preparation of the fleet to the coronation of William the Conqueror. It offers history, religion, blood, plunder, politics and conquest. For these reasons I am giving my translation of the Carmen the bigger and more accurate title: Carmen de Normannicum Conquestum - The Song of the Norman Conquest.

As I began to put history to the narrative of the Carmen, many surprising facts came to light, and many surprising patterns emerged. Some of these facts will be at odds with the received wisdom and general understanding of English history about the conquest. That is unfortunate, but progress requires the recognition of error. The Carmen is very likely right, and history as it is taught is very likely wrong. So much of what we think we know is what we choose to know. Perhaps it is time to offer a wider choice that places English history in a wider context, painted on a wider canvas.

My translation of the Carmen makes the following revelations:

- Where the Norman fleet landed on the Sussex coast;

- Where the camp was erected;

- Where the former fortification was restored and why it had been razed;

- Why certain parts of Sussex and Kent were raided and not others;

- Where the battle was fought;

- Where the thousands of Saxon and Norman dead are likely buried;

- Where Harold died and where Harold's remains were buried;

- Who approached William to seek a political settlement for London;

- The legal argument the envoy used to win William into conceding London's liberty;

- The identity of the Norman prelate at the bilingual coronation in Westminster Abbey;

- Why Battle Abbey couldn't be on the battlefield and why the alternative site was chosen.

The objective of this blog is to provide a forum for sharing ideas and evaluating theories that emerge as the Carmen reveals its own truth about the events of 1066. In like spirit to Guy de Amiens, I am happy to learn from others and to open my work to collaboration and supplement.