One of the patterns I found while researching the Carmen was the "First Christian King" pattern. Maybe historians have already written hundreds of papers on this, but I stumbled on it as an observation, so that's how you get it here. Like everything Roman there was a system for subjugation of client kings and the Roman system set the standards for first Christian kings in the Roman Catholic Church. It turns out the church took possessions it received from first Christian kings very seriously, and these possessions became key territorial objectives of the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Only kings consecrated by the Catholic Church with the consent of the pope were deemed royal with rights of inheritance for their heirs in the early medieval era. Kings sought papal approval and holy consecration to gain legitimacy and protection from challenge of rival tribal lords and neighbouring kings. The first Christian king of just about anywhere you can name in Europe will have three things in common with other first Christian kings: (1) He was approached by a missionary sent by a pope to convert him to Christianity; the missionary baptised him and established Christianity in his realm. (2) The king founded a priory for the care of his immortal soul in the Holy See, giving land and the revenues of an extraterritorial and inviolable canton port to the monks of the new religious order, usually Benedictines. (3) The king founded a bishopric for a native church with an episcopal see; the see was granted liberties and revenues of a market borough so that the native church, bishops and priests might prosper and convert pagans to Christianity. The Roman Empire had incredibly efficient systems for promoting and controlling trade and markets as the portorium and vectigalia were the principal means of streaming money from provinces to Rome. The Roman Catholic Church church took these systems and leveraged them into a stream of secular revenues for the church and Holy See that in parallel promoted the concentration of wealth and power in the Christian royal kings. If you think of it as a Mafia-style protection racket, you won't be far wrong.

In England the first Christian king was King Lucius, converted sometime around 180. According to legend he wrote to Pope Eleutherius asking to become a Christian, and the pope sent missionaries Fuganus and Duvianus to baptise the king and establish a Christian church in England. King Lucius then founded a priory in the Holy See at Dover for the care of his immortal soul, endowing Christ Church inside the old Roman castle as a priory with revenues of the port. He founded the archbishopric of England in London with a church for the episcopal see at St Peter-upon-Cornhill; its first bishop was Thean. Lucius founded other churches for other bishoprics including the Old Minster at Winchester and St Martin's church in Canterbury - each with the lands and liberties of the borough flamens for support of the church's good works and the spread of Christianity in the diocese. King Lucius reigned for 77 years, including 54 years after his baptism, and was buried in London at his death. After his death Christianity faded again, under attack by Romans and pagans alike, and the English church lapsed in the 4th century.

In 496 Pope Gregory sent Augustine, Mellitus and Justus with 40 monks to bring Christianity again to Britain. King Aethelberht of Kent was married to Bertha, a Frankish princess and Christian from across the Channel, and she sought to bring Christianity to her husband's kingdom. Augustine delivered his brothers from a tempest into the port of Wincenesel, and they danced and sang in gratitude at their deliverance. King Aethelberht was baptised a Christian, founded a priory in the Holy See with revenues of a port, and founded a bishopric at Canterbury to be the see of Kent with Augustine as the first archbishop of Canterbury, moving the archbishop's episcopal see and control of the English church from London to Canterbury.

Mellitus then converted King Saeberht of the East Saxons to Christianity, and like all first Christian kings, King Saeberht founded an abbey with a port for the Holy See and a bishopric with a see for a native church. The abbey was consecrated to St Paul in the Roman port of London, known then as East Minster and believed the site of the earlier church granted by King Lucius. The episcopal see was consecrated to St Peter on Thorn Island, known afterwards as West Minster. Mellitus was ordained the first bishop to the new see at St Peter’s Westminster in 604. Mellitus fled to Gaul after King Saeberht's death as his pagan sons sacked Westminster and London in 617. Although Mellitus returned as archbishop of Canterbury, no bishop returned to London for fifty years, and when Wine was made bishop of London in 666 he took refuge within the city's strong walls at Old St Paul's abbey church, making it the episcopal see by usage rather than endowment, and confusing royal and Holy See jurisdictions.

Aethelberht's daughter, Aethelburg, married King Edwin of Northumbria, and by 627 Paulinus, the monk who accompanied her north, had converted Edwin and a number of other Northumbrians. Like all first Christian kings, King Edwin founded an order in the Holy See to pray for his immortal soul with revenues of a port at Lindesfarne and a bishopric with a see supported by borough market and liberties at York with Paulinus as the first archbishop.

King Cenwalh of Wessex converted to Christianity about 648, establishing a see for the diocese of Wessex at the site of the church founded by King Lucius in Winchester, which became the Old Minster and later Winchester Cathedral. He founded a Benedictine religious order in the Holy See and gave them the Isle of Wight with port privileges for the care of his soul. King Alfred the Great would later establish a priory in the Holy See at Winchester, the New Minster, confusing royal and Holy See jurisdictions in the borough.

In the 8th century King Offa unified the kingdoms of England by conquering the East Saxons, Hastingas and Wessex and merging these three distinct regions with his native Mercia. His powerful wife Cynethreth was a Frankish kinswoman of Charlemagne, and the queen and his adviser Alcuin urged alignment with the pope and adoption of Frankish commercial administration and trade. King Offa sent to the pope to seek consecration as king of the united realm, later visiting Rome himself on pilgrimage. He confirmed a priory for Saint Denys at Rotherfield with the port of Hastingas & Pevenisel, known as Wincenesel to the Benedictines, and also granted the same order land on the strand at Lundenwick, the port of London. He founded a see for a new bishopric at Lichfield for the benefit of his the northern kingdom. Vikings had begun to raid England and had overwintered for the first time in England the year before, so perhaps King Offa was keen to secure alliance with the Roman pope and the Frankish emperor to better defend England against the Vikings and the Danes.

The Danes were not easily dissuaded from settlement and raiding in England and over the succeeding centuries more and more Danes settled in England. First the Danes settled in the north and east, creating Danelaw - a region under Danish hegemony. Then the Anglo-Danes of the north of England continued raiding in the south, demanding tribute from the English kings. King Aethelred decided he needed big, bad allies to take on the Danes so he married Emma of Normandy in 1002, making her queen with primacy for her sons as legitimate heirs to the crown. A few months later he ordered the killing of every Danish man, woman and child in England on St Brice's Day. Among the dead was the sister of King Sweyn of Denmark and he started invading England the next year. King Aethelred died in 1016, his son Edmund Ironside was defeated and died a few months later. King Cnut the Great married the widowed Queen Emma in 1017. King Cnut and his Danes and Anglo-Danes raided and enslaved widely in England, including taking possession of ports, lands and treasures belonging the church. King Cnut still wanted Rome's legitimacy, however, so he gave a charter of protection to London to secure consecration as king of England in 1016 and a charter of protection to the manors of Hastingas and Pevenisel to secure consecration of Emma as queen of England in 1017. Both London and Portus Hastingas & Pevenisel remained Holy See jurisdictions with exterratoriality and inviolability. The Roman Catholic Church, which controlled all international trade ports in Christian realms, would have insisted that trade with England be directed to the ports it controlled in England and the ports at London, the Isle of Wight and Hastingas would then become hugely prosperous during the decades of King Cnut's rule of England. The frequency with which Godwin and his sons raid the Isle of Wight, Pevensel and Hastingas during their rebellions against Edward the Confessor and each other are testimony to the appeal of Holy See ports as prosperous targets.

Bringing this back to the Carmen and 1066, William the Conqueror landed at Wincenesel in the port of Hastingas & Pevenisel - also known by then as Hastingaport - the very port said to have welcomed St Augustine and his chums. After the Battle of Hastings when William had become lord of England by defeating and burying the excommunicate and unconsecrated King Harold under a heap of stones on the coast, he began to secure possession of the royal realm. He marched to Dover and took possession of Dover and its port and castle, where he remained 30 days. Envoys were sent to Canterbury and the archepiscopal see of the Church of England sent the first tribute, followed by all other urban boroughs in canonical and royal duty. Then William marched to Winchester where the primates (the bishop of the see in Old Minster and the abbot of the abbey in New Minster) and Queen Edith, relic of King Edward the Confessor, all agree a deal offered by King William: they will accept him as king and swear loyalty, but they will only pay him market tolls - vectigalia - and not poll taxes - tributa. Then William marches on London where the rebels have taken sanctuary and a Witenagemot has convened to make Edgar the Aethling a figurehead king. King William guarantees the burgesses of London will retain their independent republican governance and generous liberties and they agree to renounce Edgar and swear oaths of loyalty to King William. The bishop who holds the king's right hand in procession to Westminster is Archbishop Ealdred of York while his left hand is held by "another equal in rank", referring to the metropolitan Bishop William of London, just as London and York were deemed equal by Pope Gregory in the 6th century.

Wincenesel - a Holy See port. Dover - a Holy See port. Canterbury - the archbishopric of all the church of England. Winchester - the see of the bishopric of Wessex and a Holy See borough. London - the see of the bishopric of the East Saxons and a Holy See port. London and York equal metropolitan bishoprics in canonical law. Anyone else see a relevant pattern here?

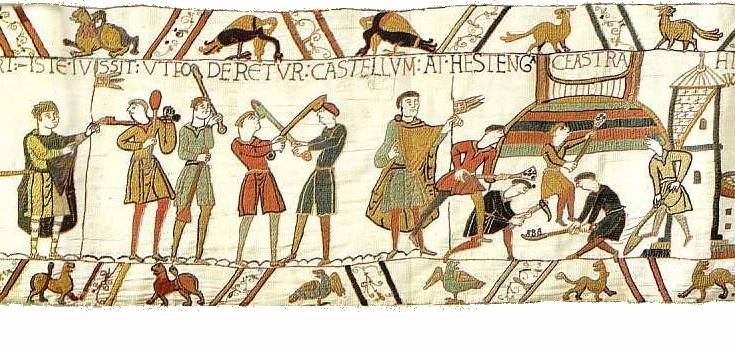

The church wanted Dover back even before 1066. Return of Dover castle was part of the oath Earl Harold swore to Duke William in 1064 when he was in Normandy. In the Carmen Dover is the first objective after securing military victory. King William put Dover in the custody of his brother Bishop Odo of Bayeux, returning the port to church administration.

Envoys were sent to Canterbury demanding tribute to King William. As an ecclesiastical urban borough in the royal realm it owed tribute and loyalty to the new king. A letter from Pope Alexander II to the clergy of England demanding canonical submission to William as the rightful king would have convinced the clerics even if the Norman army didn't. Canterbury yields the first tribue, and all other ecclesiastical urban boroughs then send tribute and magistrates to swear fealty in duty to the new king. That leaves Winchester and London as the hold outs.

Winchester had a confusion of jurisdiction, hosting both the see of the bishopric at Old Minster and the priory in the Holy See at New Minster. Showing deference to New Minster within the Holy See, King William compromises to accept oaths of loyalty and customs tolls, forgoing royal tribute. After the Norman Conquest the Norman kings forced the monks of New Minster to take residence elsewhere outside the city walls, clarifying the jurisdictions between royal realm and Holy See again.

London also had a confusion of jurisdictions, hosting the see of London at Old St Paul's church by usage from 666 and the Holy See port at the strand and the ancient dominion and liberties of the Holy See within the city from the foundation of Old St Paul's abbey in 604. King Edward may have been rebuilding St Peter's church at Westminster in order to return the episcopal see to the site originally intended by King Saeberht and Pope Gregory, and thus restore the original intended clarity between royal and Holy See domains. St Peter's church at Westminster was consecrated at Christmas 1065, a week before King Edward died and Earl Harold declared himself king.

The objectives of the Norman Conquest after the Battle of Hastings were the Holy See possessions of Dover, Winchester and London, and the seat of the English church at Canterbury. The author of the Carmen was deeply knowledgeable about the history of the Roman Catholic Church in England, and the possessions of episcopal sees and Benedictine orders. He uses the word coloni - tenants or settlers - only for the citizens of ecclesiastical jurisdictions, where citizenship was a matter of covenant and not a birthright. He uses sedem for Westminster and Winchester, both sees of the first bishoprics established by the Gregorian Mission, even though in 1066 the bishop of London was resident at Old St Paul's within the walls of the city. He references the equality of the metropolitan bishops of London and York. The overall import of the Carmen is that the Norman Conquest was a bit of a crusade to restore Christianity to England and restore the possessions of the Holy See, clarity of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, and canonical authority to the pope.

King Harold was excommunicate and unconsecrated, crowning himself king in defiance of papal authority. Archbishop Stigand was excommuniate, defying canonical authority of five successive popes to hold the see of Canterbury without pallium. He crowned - not consecrated - King Harold without papal assent. Pope Alexander II wanted them both deposed in 1066 and Duke William of Normandy was his instrument for getting the job done. The pope may not have armed divisions, as Stalin ironically observed, but the pope could declare 'open season' on monarchs he disapproved by papal excommunication.

King William reinstated Christianity in England under authority of the pope in Rome. Like other first Christian kings he endowed an abbey in the Holy See for the care of his soul at Battle. He established a bishopric for an episcopal see at Chichester (taking over from Selsey, long since dispossessed by Godwin of anything of value). He confirmed the ancient liberties of London. He restored dispossessed Holy See possessions at Hastingas & Pevenisel, Steyning, Eastbourne and elsewhere to Fecamp Abbey, an order in the Holy See. He installed Lanfranc, prior of St Etienne of Caen (Holy See religious order) and a confidante of Pope Alexander II, as archbishop of Canterbury to oversee reformation of the English church, restoring it to canonical alignment with Rome under papal authority. He invited all religious orders and churches in England to seek restoration of dispossessed lands and liberties as they had been held under Edward the Confessor, creating a free-for-all ecclesiastical forgery industry that historians are still unravelling today.

Last year the Vatican announced that it would be digitising and publishing all the ancient records in the Vatican Library, starting with the very oldest and most fragile manuscripts. If they kept records of Holy See possessions and episcopal sees granted by royal charters of the first Christian kings, we may yet have more proof that these possessions and sees were not just points in the landscape in 1066 but also a casus belli of the Norman Conquest.